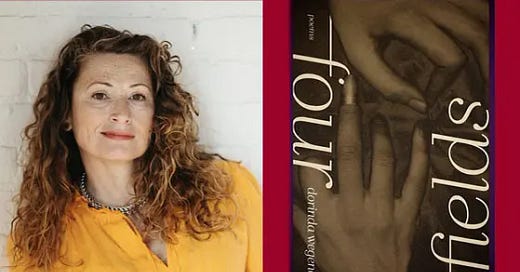

Dorinda Wegener almost walked away from poetry in 2016, after struggling to balance her love of writing with her career as a full time nurse. Eight years later, she has just released her debut poetry collection, Four Fields. I recently had the opportunity to speak with her via Zoom about life, work, art, and everything in between.

It is such a pleasure to meet you! How about we start with some background. How did you start writing poetry?

I have written since I was a kid. I have always written poetry. I remember being thrilled in third grade when my teacher handed out these notebooks and said that we would start learning poetry because all I wanted to do was write. What she really meant was we would be copying down a poem in cursive, a poem from a famous poet, and then we would memorize and recite it. I have ADHD, and needless to say, I failed poetry in third grade– I was like, "This is dumb."

Even so, I've always loved poetry; I've always written my own stuff, and about two and half decades ago, I decided that I wanted to pursue it as a career. I went through an MFA. It helped give me a sense of discipline, but it never came to fruition, so I had to get a job because I needed to pay the bills. In 2016, I actually walked away from writing. I wrote for myself, but I completely stopped submitting. With full-time nursing, you really can't do anything else– I got very into running, but that's about it. There just isn't much space to write.

I’d love to hear a bit more about your relationship with running. Do you feel like your running practices align with your writing practices at all?

Oh, without a doubt. When you're running, you MUST have a training plan. You have to put in the hours, even when you don't want to. I run when it's freezing out; I run when it's raining; I run when it's blistering hot; the follow-through is the most important thing. Poetry is very similar in that way, and it's something I struggle with. You have to do poetry in order to be a poet. You have to read constantly, engage with the literary community, be diligent in your writing. You have to keep writing, even if it all feels like garbage, because every once in a while, you get that little nugget of gold.

How did this book come about, and how did it end up at Trio House?

The book came about by the grace of a friend. It's incredible what friends will do for you when you're unaware of what they're doing. My friend got the manuscript to Trio House, and they eventually reached out to me and said they'd like to solicit the book.

So, we have talked a bit about your career as a nurse. Do you feel that your background in medicine has influenced your poetic voice/point of view?

Oh, absolutely. Four Fields was influenced by looking at the world through a scientific, microscopic eye. I am always looking in and down, trying to get to the smallest unit. I think because of that, the body is always where I enter my writing, whether it’s my physical body or it’s the body of something in nature: a bird, a tree, a deer.

I recently developed a shoulder injury and have not been able to nurse. I have written more in the past four months than I have in YEARS, and it’s given me time to really sink my teeth into my next project, which will focus on nursing. Being away from the hospital has given me time to begin processing the things I’ve seen. I nursed through the worst of COVID-19, and it was some of the most intense work I’ve ever done. This next collection is my way of sifting through all of the things I’ve seen. It’s difficult work, nursing, but I would want someone to do it for me.

That sounds like such an interesting project, I look forward to reading it. Earlier, you mentioned how much of your work is rooted in the body, particularly through nature. I really appreciated the recurring nature imagery in Four Fields, particularly the bird motif. What about the birds and flight are compelling to you?

The concept of flight is something that has fascinated me since I was a child. Growing up, you know, friends would always ask, “If you could be an animal, what would you be?” I was always the kid who wanted to fly, and I think the reason for that is that I am always introspective, always turning inwards. I love playing with the idea of flight because it allows me to go out into the macro and see the world from above.

I really enjoyed the sense of introspection in your collection. You have this talent for describing the world around you with such clarity. Was it difficult to develop that sort of precision in your writing?

The ability to communicate has always been challenging for me because I’m neurodivergent; I have a processing disorder. When I was younger, I spoke very late, although I started reading very young. I had to go to speech class, and it was very embarrassing for me, especially growing up in the seventies when bullying was sort of a rite of passage. Communicating has always been a struggle, but I’ve always found wordplay very enjoyable because it’s sort of like a puzzle. I really enjoy sonics and slant rhymes, and that is something that I’m always working on, especially when I’m revising.

The musicality, the rhythm, the percussiveness of poetry are very important to me. As a neurodivergent person, music is life— it’s such a huge part of how I connect to the world, how I focus, how I create. It’s especially interesting because I never learned meter or scansion going through school, but that sonic aspect of poetry has always been so important to me. The visual associations and imagery have always felt very intuitive, but the sonic aspect is something I’ve put a lot of effort into, and it plays a huge role in how I articulate what I see.

Another aspect of Four Fields that the four sections kind of fall into this thematic arc. Specifically with your discussions of parenthood, there is a very clear arc throughout the book from childhood to parenthood. Did you write the book with that sort of arc in mind, or did the form develop into what it is overtime?

The arc came over time because the manuscript has gone through so many different iterations. The revision process really shows why creating a community as a writer is so important because there are so many ways to approach a manuscript: it can be quite daunting alone. I have a dear friend, Terry Lucas, who is so sharp; he just sees things in a way most people don’t. He was a great help with figuring out the organization of the poems. The arc of the book came together once it had been organized into the quads.

I think the emphasis on family comes from the fact that this is a debut collection. Writers are often told to write what they know– it’s quite cliched at this point. However, there is some truth to that idea, and so I think I often found myself focusing on family for that reason.

Another significant aspect of the thematic arc of Four Fields is the idea of overcoming trauma, particularly religious trauma. I found it interesting: although you grapple a lot with the shame and guilt that tends to stem from religious trauma, there is ultimately a sense of compassion and healing. How has poetry allowed you to unpack these conflicting emotions? There is often an idea that poetry is primarily a source of catharsis for the poet. I certainly understand that this is true for many people, and I think it speaks to the power of poetry as an art form that can facilitate that sort of healing. However, for me, the forgiveness had to come before the collection. The healing had to occur in order for the poems to exist. There is still a sense of catharsis in that I feel completely unburdened. It’s like a boat: I can unmoor the boat, and I can push it out to sea, and the boat will go where it needs to go.

And beyond healing, I needed time to mature. When I was younger, I was in so much pain, and it felt much easier to place all of the blame on others than to take ownership of myself and my actions. There are absolutely ways in which I was wronged, things that happened to me that never should have occurred, but sitting in all of that pain prevented me from moving forward.

Getting older and going to therapy, learning to forgive and move forward, and allowing myself to take responsibility for my own actions are what allowed me to write.

This is your debut collection. Is there anything you wish you had known about this process going into it?

I wish I had known that the book is not the end. When the book first came out, I felt this immense relief: I thought, “thank god, I can finally relax”; there is no relaxation. The book is just the first rung of the ladder. You’re constantly promoting yourself and your book: it’s hard not to be consumed by it. I feel like an imposter so much of the time. There are these days when something amazing happens, and it completely paralyzes me because it feels like I’m not even the one accomplishing these things. I think eventually, though, you find a way to combat that. I find myself turning inward more often, going offline. I focus on gratitude, and I keep my ego in check because we all have that ego. I think that’s the most important thing to know: there will always be times when you feel like you don’t deserve what you have or when you feel like a fraud, but it’s always temporary.

What are you looking forward to?

There are a few! The first is a bit terrifying, but it is also such a blessing; I’ve decided to try to work part-time in nursing so I have more time to write. I am also very excited about the wonderful people I’ve met through this book. I’ve always been a bit of an introvert, but I adore being in a community with other writers, talking about poetry, and reading poetry. The readings, the festivals, meeting audience members, and building those relationships are what make it worth it.

For more information on Dorinda Wegener, Four Fields, and upcoming events, visit her webpage. To purchase a copy of Four Fields, please visit Trio House Press.

Annie Wyner is the Managing Editor for Carrion Magazine, and a submission reader for Trio House Press. They are a student at Oberlin College, majoring in Comparative Literature and Classics.