Breath as Song in Life and Poetry: A Conversation with Kalehua Kim

A conversation with Kalehua Kim by Cynthia Via

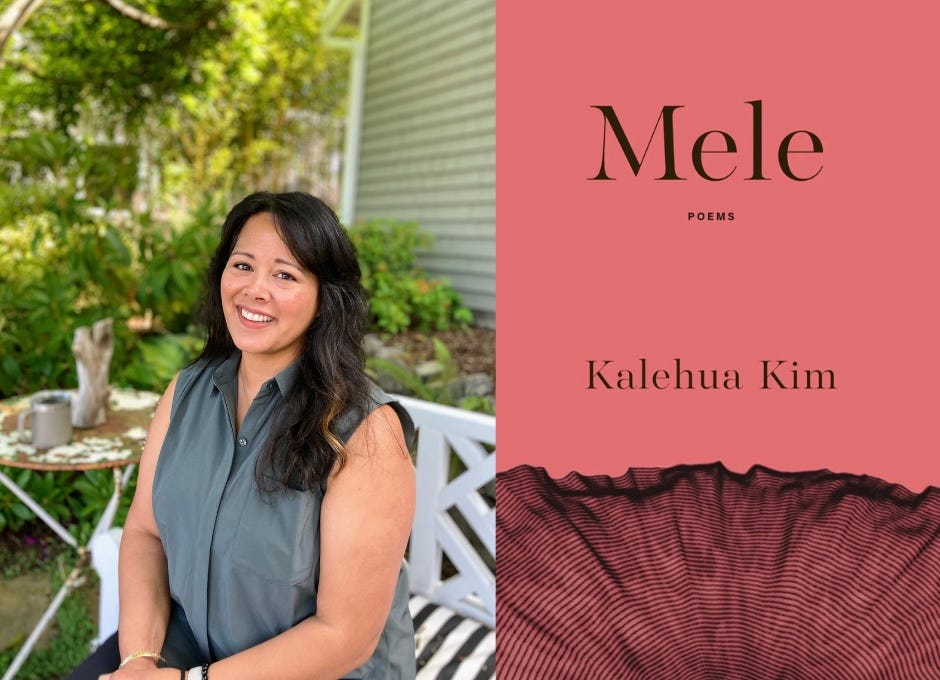

Kalehua Kim is the winner of the 2025 Trio House Press Editor’s Choice Prize. Her collection “Mele” embodies the meaning of the word—a Hawaiian song or chant traditionally used to preserve history through oral tradition. Kim’s debut collection evokes modes of language and culture that shape the contours of memory and expose the fault lines of family and self, as well as the grace and generosity of healing, acknowledgement, and commemoration.

Her collection, Mele, is available for pre-order.

In my recent conversation with Kalehua Kim, we explored how she arrived at a Mele structure to house her poems, her relationship with her mother through song and breath, and how it has evolved over time into her own life. We also dove into the feeling of impostor syndrome when our culture and language is not accessible, as well as contrasting ideas of femininity between generations.

Cynthia Via: What influenced you to organize the collection like a song structure found in Hawaiian songs or chants?

Kalehua Kim: This is my first book. It has material from a long time ago and very recent material. So it was difficult for me to figure out the arc of the collection. How do I make the previous versions of myself come into contact with this version of myself that's still deep in the grief of losing my mother, and how do I relate that to an evolving self? So I looked at the material and realized there was so much music. So, thinking, what is the foundation of music for me personally? And, how does that relate to how this information was handed down to us from generation to generation? In Hawaiian culture, there is so much ingrained music. It’s an oral tradition, so songs are handed down, and it's a way of holding onto your history and acknowledging it, but also celebrating it in music. Once I found all of those themes across, and especially thinking, what is this thing that my mother gave me, and how do I remember her the most? My mother was a singer. She knew Hawaiian culture and chants and songs, but she also sang for tourists in a show when she was young, so it was a little bit more commercial. She also loved Hollywood musicals, and passed that love onto myself and my siblings. And so it was a way of holding all of those concerns and themes.

I didn't find [the structure] until pretty late into the sequencing, because I tried all these different things. We’ll do it chronologically, or we'll do it thematically. But once I tapped into that song structure, that’s when everything else found the right fit.

CV: There’s mention of the breath in and out in Glottal Stop: My Mother’s Last Words in the lines, “with breath in/song sung out/breath against/the inside of/my mouth.” Can you speak to how this art form of singing embodies the relationship between you and your mother throughout your time with her?

KK: I came to it a little bit backwards, especially incorporating the breath, because towards the end of my mother's life, she was non-verbal. She had a stroke at sixty, and she didn't pass away until she was in her mid-70s. So she had a stroke and had limited language, then had built up language, and then when she had her final stroke, she was non-verbal.

Hawaiian language is a very vowel-heavy language, and there are many places where there are a lot of stops. So you have maybe two vowels together. So like even the word Hawaii, it's hah-VY-ee, and in between the “i,” there's a diacritical mark called an ‘okina. So you're supposed to pronounce the word Hawai’i, like the i’ are “eeee.” It made me think about foreign languages in general, but also my mother's affliction. The grunting she used to communicate. She would motion with her hand instead of fleshing out a word. That was the language she had access to at this end stage. Once I thought about that, it opened up to all the languages that she and I've communicated in throughout my life. Many of those are linked to music, whether it’s a Hawaiian chant, or something we danced to like a hula with a song. There are a lot of funny things. Maybe you do this with your friends, but there's a common lyric that the two of you know. And instead of saying it, she'd sing it. It was interesting to think about language at its most rudimentary form, and then work backward into what is this relationship we have? And if language is the basis of it, how many different languages are we speaking? They're not even different languages based on geography; their languages are based on common experience, whether it's joy or pain, or even if we were separated.

CV: Can you speak to how the verses of the collection inform each other? Is there a back-and-forth conversation between the two?

KK: It’s not necessarily a back-and-forth, but there's a progression. The first verse is definitely based on a grounding of who I am, based on who she was, and what she handed down to me. And then the second verse is what do I do with that now that I'm in this marriage? My husband and I have been married for twenty years, but my parents split up when I was young. So how do I take all of the things she taught me and all of the things that I observed from her pain of not being able to sustain a marriage with my father, and how do I transfer that into my own marriage, or any relationship I have? My father left, and my brothers are a lot older than me, so my mom and I lived together for a long time. I'm only used to this sort of long-term relationship with this person who is so intrinsically mine—she gave birth to me. And we have all of these common things, and then you have a partnership with somebody else who's completely different.

My husband is from a different culture. How do I adapt that core understanding of what it means to be a partner to this other person who doesn't have the songs or the language I had with my mother. For me, that was kind of the differences between the two verses, and hopefully in the end of the second verse, it shows this is me trying to figure out how to carve my own song with this person, to make my own song, while still holding on a little bit to the core of what my mother taught me.

CV: Often, inheritance from our family exists through language and culture. What barriers did you discover as you tried to bring that into your collection?

KK: Mostly my lack of access to Hawaiian language. I was born in Hawaii and lived there until I was around nine or ten, with my mother and her new husband. Her husband got a job in California, and so my family kind of split apart. So my brother and I left with my mom and my stepdad to California, and my two older brothers stayed in Hawaii with my dad, so we would all go back and forth to see one another. But because I'm the youngest, I didn’t have as much exposure to Hawaiian culture as my older brothers did, and so sometimes I'm frustrated by my lack of understanding, and lack of language, my use of Ōlelo Hawai’i and of pidgin (Hawaiian Creole English).

Poetry is me trying to find a way back into that ancestral language. It was difficult for me to give myself permission to write in those languages, because of this feeling of not being Hawaiian enough, because I don't live there, and I don't practice these cultural practices every day, or because I don't speak it fluently. So those were definitely aspects that I had to work out with myself to give myself permission. This is your way of entering this language that is part of my life and my culture. It's a difficult place to be. I don't want to go to Duolingo. I want to learn it from my family. I want to learn it from people within my community, but I am geographically removed from them, and so I can't do that. Once I started [writing], it felt like this is a way for me to sing part of my own song. It may not look like the song of my mother or the song of my ancestors, or even of my siblings, but it's mine, and it feels okay to mix them with English.

CV: That’s definitely something I think about. I speak Spanish, but not as fluently as my parents or my cousins. So when I write poems in Spanish, I ask myself should I be doing this? I don't live in Peru anymore.

KK: The more I talk to people who are removed from their ancestral culture, the more common this theme comes up, and I wish we talked about it more. And I have heard people talk about impostor syndrome. And for me, I respond negatively to that, because I'm not trying to be something I'm not. I'm trying to be wholly who I am as a person made up of all these different cultures in these different places. I just want to connect in a way that feels authentic and respectful to that culture. There are always going to be people who say, “you didn't do this, or you're not enough of this, or you haven't put in the time, etc.” They want to find some sort of legitimacy to put you into. And I have to sort of tune that language out, because that makes it hard for me to want to connect. Because then you're like, I shouldn't even try. It takes something away from me that I feel entitled to. I am entitled to explore who I am and where I come from, and just because it looks different from what other people imagine it should be, should not negate its importance.

CV: Was it challenging to write about the loss of your mother while also thinking about self-care? Were there any emotional moments you didn't realize you'd encounter, and how did you choose which ones to include in your poems?

KK: Every, every poem. Well, I'm also a very emotional person. I could break out crying in this interview, but it's because you care so deeply, right? It was very emotional to try to connect with the feelings I had, especially while she was ill. But one thing that I love about poetry, and why I keep returning to it, is that I think it can hold all of those things for us. Poetry is so beautiful in that it can be a place to hold grief and joy in the same line, in the same home. And so that made it a safe place for me to explore. There’s one poem that I really love, because it was so hard to write. So the poem “After Her Funeral, I Dream That My Mother Tells Me Her Dreams, is all in pidgin. I struggled, because I really wanted to try to figure out, what would my mother's voice be like, if I'm trying to connect with her? How would she talk to me right now? And I was trying to write her voice as like a haiku, sort of sage, sort of Zen, peaceful, very succinct yet evocative voice.

But it wasn't working. I worked on this thing for days, just trying to connect to her in a certain way. Then I realized I was forcing that, because I wanted her voice to come to me in a way that was instructive in how to deal with my grief, and I was forcing it into a form. And I said, why don't I try and write it in the most basic way we could talk to each other, and part of that would be in pidgin. Then it just came once I let go of an expectation of how I wanted the finished product to be.

CV: Yeah, it's difficult because we're constrained by language, and we're so conditioned to using language a certain way. And when you know how to speak pidgin, or colloquial speech, you have to break out of those boundaries you’ve been taught in school.

KK: There's a certain sense of legitimacy, right? I need to speak a certain way, even on the page, so that it's widely acceptable for readers. For me, it was like, I have to reclaim pidgin, or my place of comfort. For me, it's more about the rhythm of the language versus what's actually being said. The rhythm has to match the feeling of the song that I want to convey, instead of the specific lyrics.

CV: That actually segues into my next question. In some of the poems, you're using language to create your own form, like in the poems Hā, We Fall and Makali‘i and the Stars That Followed. How is the language syntax and repetition interacting with form? How do you know that the form is authentic, an authentic part of the poem, and not a deviation?

KK: With the first two poems, I'm not thinking about form at all. I'm solely thinking about rhythm and cadence, especially for those two. With Hā, meaning breath of life, I’m thinking a lot about breath and the rhythm of breath, and how one breath leads into another, so one line leads into another. It's sort of associative in that way. So I'm not thinking about form. I'm thinking about just going where the breath takes me, basically. And it's kind of the same with We Fall. In Hawaiian music, there is a lot of repetition because it's an oral tradition. It’s a way of remembering so we can pass it down, and it's often set to a drum beat or a gourd, helping you remember those words and what comes next in the cadence. So those are two great examples of rhythm specifically driving me. It was in revision where I started to think about what I'm actually doing. I'm actually repeating the line and adding to it. So in Makali‘i and the Stars That Followed, which is actually a duplex, a Jericho Brown form, where he repeats lines within a certain syllable count. I think that's why it was also appealing to me to try to utilize that form, because I like repetition. I like that there's a certain rhythm to it, and the first line will be the last line. I love the cyclical nature of it. I hadn't thought about it before, but yes, those are all very rhythmically driven, and then form comes after, at least for those examples.

Part of my process is reading everything out loud multiple times. It has to feel right with the breath, and it has to sit right in my mouth. And then I can look at it from a syntactical aspect, or the word choice.

CV: I noticed an unexpected darkness in some of your poems like in Offspring, Brooding, and the Joy of Raising Chickens. “If I push my pen/ across this page, would/ the letters leap/ or bleed into my fingertips, heavy/ and dark as my mother's wet stone.” How does darkness enter light-hearted beginnings, or what we think of as light-hearted subjects, like chickens?

KK: I don't think of it as being dark, really. It's just part of the balance. When there's levity, there needs to be something to ground you. I do have chickens, and I spent a lot of time hanging out with them during the pandemic, just sitting in the yard and watching the chickens. And there are so many things, especially around mothering, that follow chickens like, mother hen, the pecking order. All of those colloquiums we have, or phrases around chickens, are true. We had four, and there was definitely one who was the mother hen, and made sure everyone did what they needed to do. It was interesting to watch them interact. And, they are funny. They're hilarious creatures, but when they're serious, they mean business, like, the first one to get to the food is the one that's going to survive. They're beating each other out, and in the next moment, they're pecking at each other, or they're grooming each other, or dust bathing together. I became fascinated with their interactions and how that’s a kind of microcosm for this grief. There are moments where it feels okay to continue, and then other moments, when I think about something, a song I've heard, and I want to call my mom and tell her about it, and she's not there for me to do that. So there's the joy of the song, there's the joy of learning something new, and there's the darkness, or the seconds of not being able to communicate with the person you want to connect with. I feel there's a balance, and I hope there's a balance in the book.

CV: In the poems KS Class of ‘57 and Impression, you remember your mom through feminine moments of putting on makeup and leaving blotted kisses on your face. But you also write, “We all we each, becoming women. Becoming something, someone somewhere decided was a woman.” Being of a different generation, how do you view your mom's femininity, and how do you express yours differently?

KK: I love this question because my mom definitely grew up post-war in the 50s, and there was a lot of emphasis on image. She told me how when she was younger, it was a fad to shave your eyebrows and draw them on very thin. As she grew up and the fad went away, her eyebrows didn't fully grow back, and she always had to draw the rest of them. She would always talk about, I should have them tattooed. She was always concerned about looking a certain way when she went out in public. It was always a full face of makeup every day. She did her hair. She dressed a certain way. Her clothes had to be pressed. But then also because of growing up in Hawaii after the Second World War, this aspect of assimilation plays heavily into that as well. How do we look so we can assimilate into the mainstream white culture that has taken over our home? That stayed with her for a long time. Even when she was in her late 60s and 70s, we would go someplace, and she’d say, is it okay I'm wearing jeans? She was prematurely gray in her 20s, and colored her hair up until she was almost seventy, and then she finally let it grow all out. I don't think that she ever overcame those expectations in her lifetime.

For me, while I'm still very grounded in that, I'm working every day and being okay with sometimes not being fully put together. When I leave the house, I try to have my hair brushed and my teeth brushed— have a little face on. Living in the Pacific Northwest—I’ve lived here for over 25 years—it’s very different from the Bay Area, where I spent most of my years growing up. The weather is kind of severe. It's cold. People are wearing parkas all the time, and it's a little bit granola up here, so people don't really care. That took me some time to get used to. I grapple with that sort of self-image based on how she dealt with assimilation through image, and that's something I continue to explore.

I have two daughters, and they have a completely different sense of style than I do. I’m so happy and excited about that, because they're doing the things they're comfortable with. It sometimes causes me discomfort, but that's part of the learning. They're their own people, and they're gonna sing their own songs. I'm just really grateful that I’m still in a place where I can learn from it and not judge my mom too harshly for those things, because our parents and our grandparents and ancestors, they were doing the best they could with what they had at the time. So I try not to hold that against my mom too much.

CV: In all my excitement, I forgot to ask, what’s your favorite Hawaiian chant or hula song that you shared with your mom? Or any song you remember sharing with her?

KK: I inherited my love of musicals from my mom. We'd spend many Sunday afternoons watching movie musicals on the Turner Classic Movies channel. One of her favorites was "Carousel." My older brother remembers watching it with her as well, and went on to record a song from the show called "You'll Never Walk Alone" with his band. He translated it into Hawaiian. My husband and I used it as our first dance song at our wedding, where my brother sang it for us. I love the way that song evolved for my family. It's still a treasure.