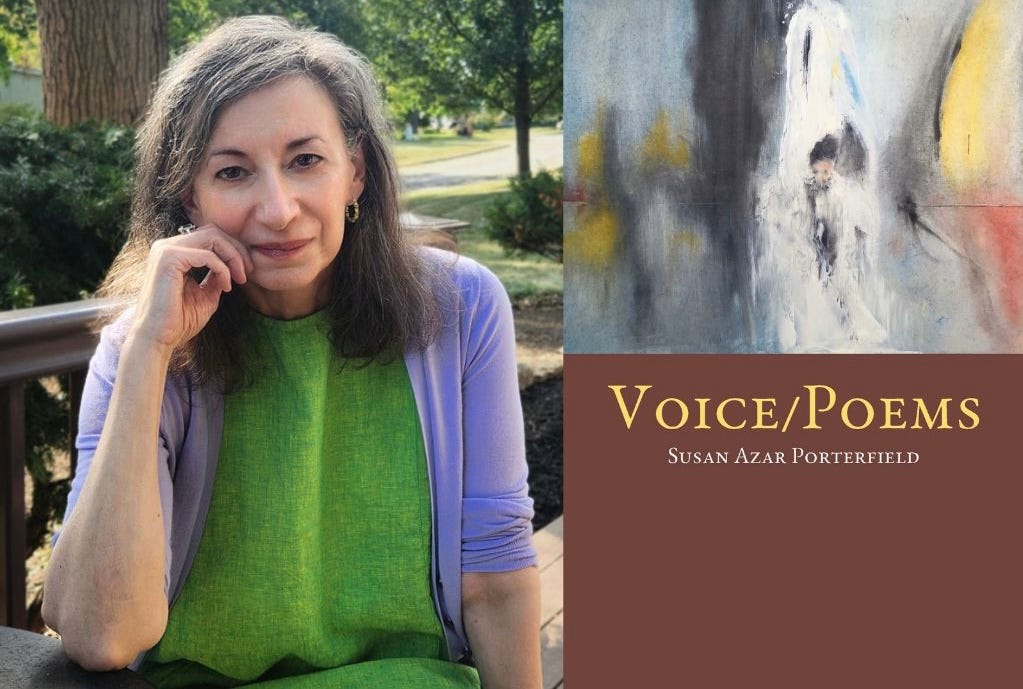

Voice/Poems: A conversation with Susan Azar Porterfield

A conversation with Susan Porterfield by Richard Terrill

In our recent conversation, I asked Susan Porterfield about her process(es) in creating poems and in shaping a wide range of themes into a successful collection. We also talked about how dreams, the mysterious, and concerns with the suffering of living creatures, enter into the work.

Richard Terrill: You’ve made an interesting choice to include the title poem “Voice,” about a child hearing voices, near the beginning of the book, and then to repeat lines from that poem to introduce each of the four sections of the book. How did that choice come about?

Susan Porterfield: I’m very interested in the concept or idea or construct (I’m not sure what to call it) of poetic voice. Sometimes a novice poet is told that they need to “find their voice” or they’re reassured that they will, indeed, eventually “find their voice” as if this voice is uniform, unchanging, singular. Maybe it is. Maybe not. Years ago, I looked up “voice” in my lovely, huge, comprehensive Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, which I still have from my Intro. To Poetry class. Hmmm. No entry. “Zéjel” is there. So is “Zeugma.” But no entry for “Voice,” unless you flip to the Supplement. And there it is, an afterthought, a somewhat helpful entry but hardly definitive. What further intrigued me about voice, personally, is that I found, when I began writing poetry, editors seemed more receptive to those of my poems that, I here acknowledge, tend toward the Romantic. Yes, I have that in me, and I’m not ashamed! But I can also be acerbic. They didn’t seem to be as interested in those pieces. And what about persona poems? Whose voice is that? So, while I continue to delve into the notion of poetic voice, I think I can say that a poet may have, can have, more than one voice.

RT: I so agree with you that poets can have more than one voice, even in a single collection. Voice is a slippery term, indeed.

One thing I admire in the book is the way you use poems to challenge the reader. I find this especially true at the endings of poems. Often last lines seem to imply more than they state, almost as if they’re ending with ellipses . . ..

SP: Something I want to do with my poetry is to include, acknowledge, involve—whatever you, I, we want to call it—the reader. Just my personal opinion, but, for me, art assumes an audience. The audience may be in your head, your mind, a result of your reading experiences, etc., but it’s still there. I’m not writing for Shakespeare or Keats or Eliot or Levertov, for example, but, yeah, I am. I can’t get away from them. But I’m also writing for any lovely reader who happens to pick up my book. I’d like to let them know that I know they’re there.

I think that one of the ways this notion of mine manifests itself in my poetry is in how I end a poem. Yeats famously said a good poem ends with a click—or something like that. Well, yes, I can see that. How reassuring to a reader, yes? The world falls into place after all. But his time was different and sensible. I also like the ending of a movie, for example that leaves me hanging, that opens the door rather than closes it, that encourages me to think. In fact, I like it best if you can combine the two ideas: end poems with a click, okay, but maybe with a click that’s soundless?

RT: I like the notion of the poem opening up at the end instead of closing down. It’s a question of nuance, subtlety, right? Eschewing a last line that’s like a cymbal crash? But if we’re not so worried about losing a reader in our subtlety, I wonder if we’re writing for an imagined, ideal reader. I think that’s okay, by the way.

The book features two sections made up of a series of closely related short poems; one per page. I especially liked the House series. We become aware of “porosities,” to borrow from another of your poems: the spaces within something, like the spaces between short poems. I guess this is another way of challenging (respecting, engaging) the reader. What does a poet gain from this construction that’s not present in a longer, self-contained poem?

SP: A series of poems allows the reader to meander. Being able to meander, to me, means that you have the opportunity to be more comfortable or secure as you read, still challenged but not quite as much perhaps. Books of poetry, as opposed to fiction, for example, are peripatetic—you never know what you’re going to get, one poem about snakes followed by another poem about the time you were in Paris. Don’t get me wrong, I like that about poetry. It’s just that poems that are in a series, being linked, create a different kind of suspense. How will this poem fit into the sequence? I hadn’t thought about it before, but it occurs to me that a sequence also changes the pace and rhythm of the overall book.

RT: What you’re calling meandering on the part of the reader I might call leaps in subject made by the writer. My favorite example of this is “Once Out of Nature,” which borrows its title from Yeats. On a single page we get seven sections, two to five lines each, in which the subjects leap from a celebration of the body, to a mother chimp and her young, to sleeping on a winter night… and them wait, there’s more! An encounter in a parking lot, March, a widow at a funeral luncheon, the speaker’s sister’s children. And yet when I read it, I feel it makes perfect sense. I love this.

SP: That poem does allow a kind of meandering too, I guess, in a way that a more tightly constructed poem wouldn’t, let’s say a sonnet for reference. “Once Out of Nature” wants to give several, discrete examples of how human instinct/drive/hormones—whatever we want to call it—affects us. The piece begins with the human body and celebrates it, because it is, indeed, a miracle, but we’re just as determined by it as chimps are by their bodies. They are instinctive. So are we, and it’s easier to see how this drive works in animals than in humans, perhaps. Fewer filters. So, the poem talks about the drive to procreate, how seasons instinctively affect us, the will to survive, to continue. We humans exist and are, to some extent, controlled by or at least are deeply influenced by nature, for sure. Would be nice to think that “once out of nature” means we become art or artifice, as in Yeats’s poem, but I’m afraid it doesn’t work that way.

RT: Interesting. I picked up on some of this, but to me the important part is how well the poem works even though I didn’t see all the connections. It gives me room to participate in the poem, reflecting your concern for “the reader” which you cited earlier.

Let’s talk a bit about content. I notice, especially in section one, a concern with suffering—human suffering, but also the suffering of animals: the death of a nine-year-old girl, but also a neglected neighbor dog. One poem is called “All God’s Creatures.” Do these concerns keep you awake at night (when a lot of us, I suspect, are having trouble sleeping)?

SP: Yeah, yeah, they do. In fact, the poem I just mentioned, “The House Teaches Her about Love,” resulted from a dream I’d had about trying to keep children safe and how inadequate I felt about being able to do that. I know, for a fact, that I had that dream as a result of seeing those terrible news stories about immigrant children, from all over the world, washing up dead on shores, starving, crying for their parents. And it’s about how impotent we are, ultimately, to help or how impotent I feel I am, anyway. There’s always something you didn’t think of, some new threat, which doesn’t mean that you give up trying in your way, though sometimes you feel defeated.

But especially in the first section of the book, my pointing out suffering is also me being rebellious, which is why these poems are in the section entitled “A Laughing so Sharp.” I don’t see why suffering has to exist. Don’t buy the religious argument for it. The poems, like “Death of a Nine-Month-Old Girl, Not My Own” and “Some Dog is Barking” are meant to show that we’re all in the same boat, whether the child is yours or not, whether the suffering is human or not.

RT: You mentioned your dream leading you to write “The House Teaches Her about Love.” I note that the three “House” poems leading up to this one also reference dreaming. The first is titled “Dream Room.” In the second the speaker seems to be having one of those dream moments in which she’s running but not getting anywhere. The third is set in a half awake/half asleep state where the speaker feels her own body strange to her.

And in the title poem “Voice,” the speaker hears mysterious voices while “pressed against the ragged seam of sleep.”

SP: What can I say, I like Bachelard’s Poetics of Space—nevertheless, the first poem “Dreamed Room” is indeed about a room that I visit now and then in my dreams. I’m told that lots of people have this kind of dream. In fact, this dream is so common for me, while I’m asleep, if I find myself there, I tell myself, “Oh, here I am again.” My husband says that the room represents one’s untapped potential; you feel that you’re not using your talents or capacities to their fullest—it’s a beautiful place that your psyche or whatever, imagines as a room.

“The House Teaches Her about Death” was also a dream—a friend had died, and this was the dream I had the night I was told of his death. I’m partying, he’s outside (inside/outside thing going on here), and I can’t get to the door to let him in. When I look up again, he’s gone, and I realize that I may never see him again, so I run upstairs to open the door and look for him. I see him and run after him and am just about to touch his back when I wake up. Thing is, the dream makes clear to me that there is a “door” between the two worlds that can’t be opened, a person you really can’t touch again, no matter how close you are to doing so in the dream. The dream exists to teach you about death.

I wrote “The House Becomes Strange” after my mother died. She died in the middle of the night; we think it was very quick, and perhaps this was her experience of it. But the poem doesn’t have to be about my mother. I think that the body can become like a stranger at any time. At any time at all, regardless of age.

RT: In other poems we encounter ghosts, mysterious strangers, and unexplained events. God makes a few appearances as well. Are these prompts that started you on the writing process, or did these figures arise as the poems unfolded?

SP: Sometimes it’s hard to distinguish the prompt from the poem unfolding.

In a poem like “Voice,” I wanted to write—have wanted to write for a long time—about how when I was a child, I once or twice heard a voice that seemed to come from outside of me, and this only occurred when I was half-awake. I guess this is fairly common; it’s called hypnagogic hallucinations. Regardless, of the four voices the poem records, I heard a voice telling me not to be afraid and then also a frightening laughter, which my parents told me probably came from outside my window on Chicago Street. However, I have relatives on both sides that were pretty firmly aligned with the mystical world, and they heard voices and had visions and believed in such things. My aunts and grandmother on my mother’s side were Pentecostal. They were on good terms with the spirit world! And my Lebanese grandfather told tales, such as how God spoke to him and told him to get out of the tent he was in (French Foreign Legion) right before it was attacked. So, to me, hearing voices or experiencing other kinds of “unique” encounters isn’t that odd.

Richard Terrill’s most recent books are What Falls Away Is Always: Poems and Conversations and Essentially, a book of essays, both from Holy Cow! Press. He is the winner of the Minnesota Book Award for Poetry and the Associated Writing Programs Prize for Nonfiction. He is Professor Emeritus at Minnesota State, Mankato, where he was a Distinguished Faculty Scholar, and taught for many years in the MFA program in creative writing.